Parallel computing approaches for CFD

When it comes to parallel computing, there are many ways to solve any complex scientific computing problem. Some are more suitable than others. The method and approach should be determined on a case by case basis with an understanding of the computational algorithm and data structures involved. In this series of articles, I will describe the different parallel computing approaches I have used for computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations. These provide examples of widely used approaches and I hope that they will help the reader to parallelize their scientific computing programs. I assume that the reader is familiar with the basics of MPI and OpenMP models of parallel computing.

We shall look at the following approaches:

- Slab decomposition with MPI * e.g. Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS), Poisson equation solver

- Pencil decomposition with MPI * e.g. DNS, Poisson equation solver

- Solving a large ODE system in parallel - using MPI, OpenMP, Hybrid MPI+OpenMP * e.g. vortex sheet evolution

- Graph partitioning with MPI * e.g. unstructured mesh CFD

- Coupling two MPI parallel applications

The first case I will discuss is the ‘Slab decomposition’ strategy.

Slab decomposition with MPI

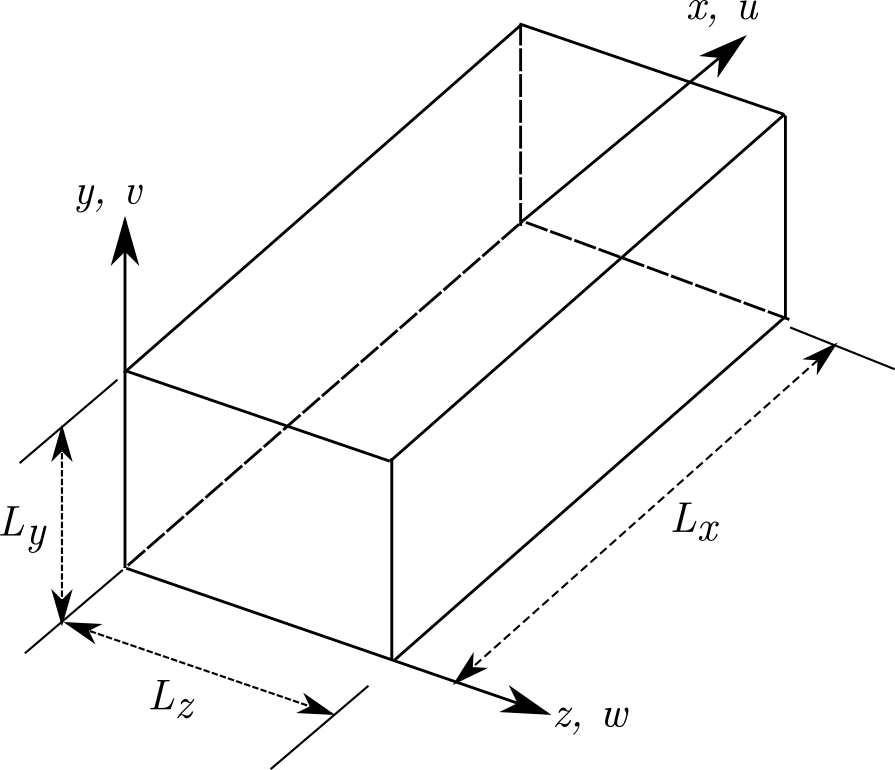

I used this approach in my Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) code to simulate turbulent boundary layers. Essentially, we need to simulate the flow in a box as shown below.

And the aim is to simulate this flow using as many processors as possible. I chose the MPI (the standard for distributed parallel computing) approach. The processors work independently in this model on their data and communicate with each other when they need to exchange data/information.

In this problem, the computation needs to be performed for every point (discretized) in the rectangular box. Fortunately, all the parts of the box have almost the same amount of computation/workload. There are special treatments required for the bounding surfaces for boundary conditions. But this is very minor compared to the majority of computational workload at individual points. So, it makes sense to divide the flow domain into equal parts and distribute the parts among processors. This is critical since if one of the processors is overworked, it would create a bottleneck for other processors continuing on with their calculation. Note that the computation is inter-dependent and exchange of data is necessary (to be discussed later). The act of making sure each process handles an equal share of the computation and no bottlenecks arise due to this division of workload is called “load balancing”. In this particular case of flow in a box, it so happens that dividing the flow domain equally would lead to equal workload for each process.

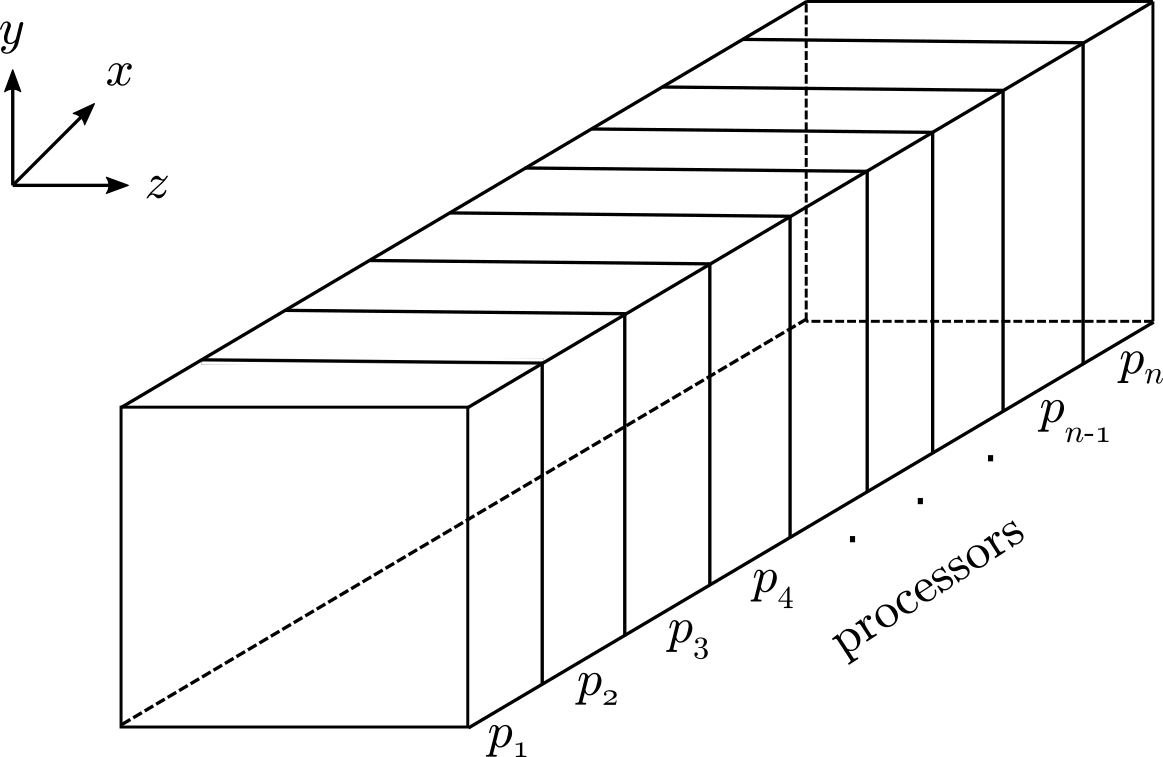

So, how does one go about dividing the box domain so that the processors work efficiently together? A well known approach for such simulations is the ‘slab decomposition’ shown below.

We split the entire domain into ‘n’ slices in the x-direction, just like cutting a loaf of bread. Each slice will be given to a processor/core. The grid and variable values associated with a given part is available only in the processor owning that part. Throughout the simulation, we expect to maintain this association.

If the slices are totally independent of each other and can proceed with their part of the calculation without depending on data from neighbouring slices, then the job is literally done. But this is not usually the case. The calculations in a slice will depend on neighbouring slices which reside in another processor’s control. Particularly, it would be necessary to access at least the data from points on the neighbouring slice’s surface. The idea of ‘halo cells’ is introduced for this purpose which stores the neighbour’s data (only the required part). How this data communication is handled is very important as it will play a crucial role in overall speed of the simulation. It is possible in MPI to introduce what is known as “Cartesian topology”. This will help considerably in the ‘halo cell exchange’ of data from neighbouring processors.

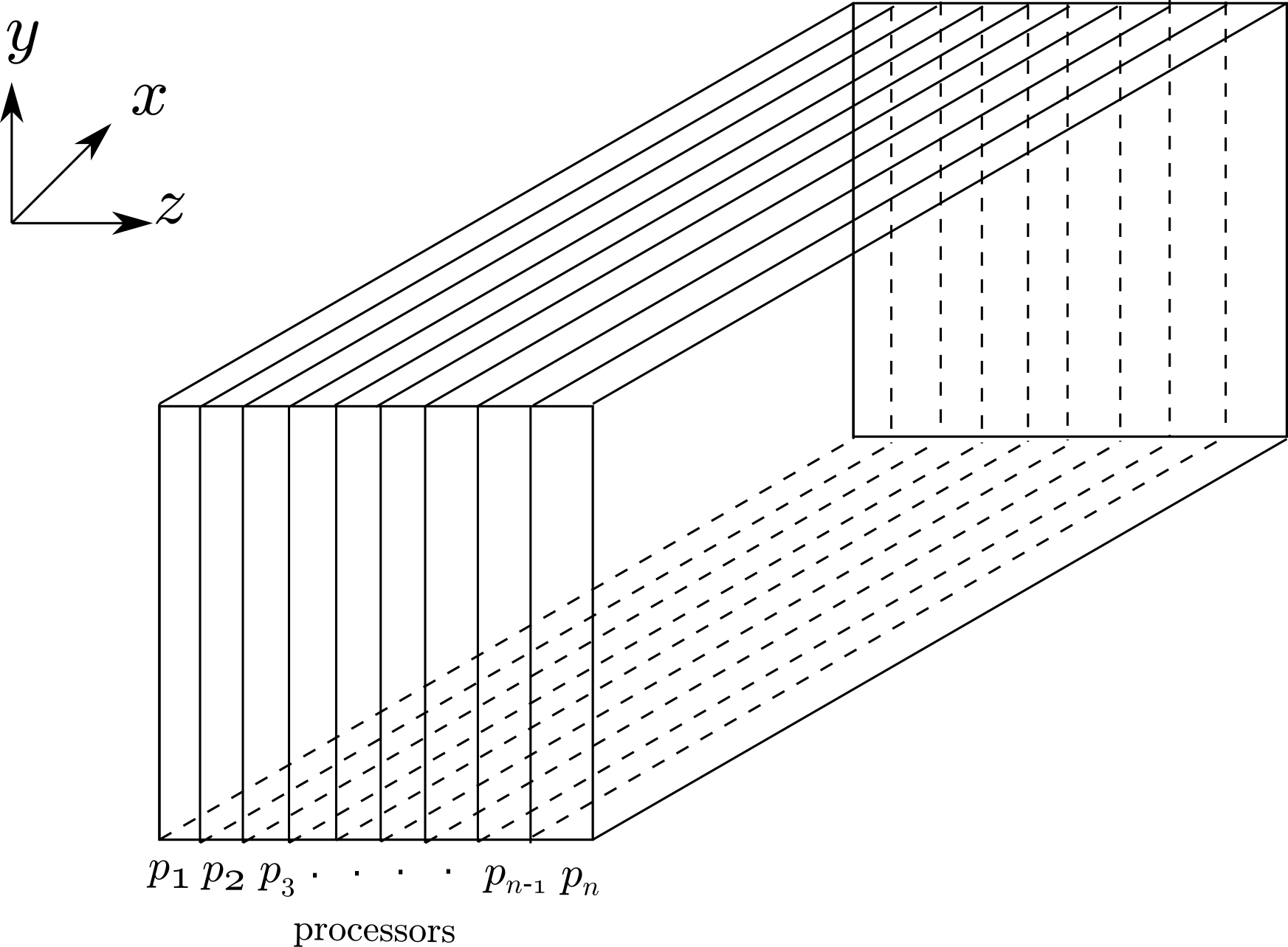

Additionally, there may be parts of the simulation where it might be necessary to have the slab decomposition done in another direction instead of the original x-direction. For example, the slabs created in the z-direction is shown below.

To achieve this configuration, we have to ‘transpose’ the necessary data from the x-wise slabs to z-wise slabs. Lots of data exchange/communication is involved in this process. So, it would be wise to do this only when absolutely necessary. ‘Transposition’ should be done efficiently as well.

(to be continued…)